Wander through any museum and you will find examples of a genre of art called still life. A still life is an arrangement of objects that each have significance. Frozen in time and connected by careful placement, a still life assembles objects that memory animates.

We all know the power of a single object to hold a trove of memories. A pressed flower from a wedding bouquet, a baseball card, a mahjong tile, a pay stub, a piece of jewelry, a postcard. Ordinary objects can contain extraordinary stories.

We all know the power of a single object to hold a trove of memories. A pressed flower from a wedding bouquet, a baseball card, a mahjong tile, a pay stub, a piece of jewelry, a postcard. Ordinary objects can contain extraordinary stories.

This project puts the memory-power of objects and the ease of photography together so that you can share a part of yourself with your B-Mitzvah grandchild — and they can share with you. The activity is designed so that you and your grandchild work on constructing a still life individually, photograph it, and then share the finished products with each other across a family table or a Zoom screen.

Whether you live nearby or a half-world apart, the project bridges decades and distance. It allows you to continue to develop a Jewish relationship with your grandchild, while learning more about each others’ lives.

Your goal is to use objects that are meaningful to you to design a photographic still life that gives us a sense of who you are.

There are five steps: Select, Compose, Photograph, Share, Display.

Step 1: Select

- Grandparent: Choose 3–5 objects that signify key moments or turning points in your life or that tell us something about you or others who impacted you.

For example, you might choose a passport that tells the story of your travels, a letter of acceptance for a school or job, or an invitation to an event that changed the course of your life.

Among your selections, include one that expresses your connection to Judaism, such as a prayerbook with a bookplate from your own Bar or Bat Mitzvah or a mezuzah from your first house, or even a pair of shoes you wear to synagogue.

You might choose to organize your objects according to dates or points throughout your life (a timeline) that help isolate key moments, feelings, or decisions that you want to spotlight.

- Teen: Select objects that reflect your character, passions, groups in which you are active or volunteer, or past experiences that have helped shape you.

You might both decide to use a symbol rather than a specific object to illustrate a period in your life. Metaphoric objects also carry the weight of memory. A playing card or pair of dice can remind us of the luck of the draw; a compass or part of a map can signify being adventurous; a magnifying glass might show curiosity or wanting to see things more clearly.

Some objects can have multiple meanings: a feather could represent blowing about aimlessly, floating along with carefree abandon, or even being buffeted from one place to another. A piece of rope can represent salvation, a lifeline, or something that binds and constrains.

Among the items, you can opt to include a photograph. (It’s easy to rely on photos to tell your story; this project is about the wealth of memories that objects can hold. Objects are often the emotional starting point for a good conversation.)

Step 2: Compose

After you’ve chosen the objects to visually and symbolically show who you are, arrange the items in preparation for photographing them. Look around for props to enhance the selected objects; for example, books to vary the objects’ height and fabric or a garment to place the objects on to create a layered look. Think about texture and form as well as placement. Remove distracting clutter.

Step 3: Photograph

- Ideally, try to be in the photograph along with your arranged objects. That personalizes the memory and shows the connection between you and the objects. You would then need someone to take the photos (or use a selfie stick or a tripod or set a photo timer in your phone camera app.)

- Take a series of photos from different points of view. Try different distances and backgrounds.

Test out natural lighting to avoid using a flash which might reflect on glass or a mirror. Be mindful of what is behind you and think about the environment. Your light source should be facing you and not behind you. If your objects are easily transportable, try to take the photograph outdoors in order to receive the most natural light possible.

Test out natural lighting to avoid using a flash which might reflect on glass or a mirror. Be mindful of what is behind you and think about the environment. Your light source should be facing you and not behind you. If your objects are easily transportable, try to take the photograph outdoors in order to receive the most natural light possible.- Consider positioning yourself in front of a significant piece of furniture, painting, bookshelf, desk, or garden. This can add interest to the photographic portrait. The objects would be on a table in front of you. If you would like a plain backdrop, you can hang up a sheet or plain tablecloth.

- If you’d like, experiment with editing your photo afterwards. For example, perhaps make it black and white if the objects are old.

- Select the best photo to share with each other and to print out. Make sure to choose a high-resolution version of the photo.

Step 4: Share

- Once the photographic portraits are completed individually, it’s time to plan a specific time and place for you and your grandchild to meet. Whether you are speaking across a table or on a couch or sharing via long-distance Zoom, it’s important to plan the time when you can listen and talk to each other.

Allow time to share equally during the time you are describing the objects in your piece to one another and explaining their meaning. Allow as much time as each person needs to describe their project, ask questions, and respond. You may decide not to interrupt each other or that it’s okay to ask questions at the end of each description

Allow time to share equally during the time you are describing the objects in your piece to one another and explaining their meaning. Allow as much time as each person needs to describe their project, ask questions, and respond. You may decide not to interrupt each other or that it’s okay to ask questions at the end of each description- You may choose to end the conversation by asking probing summary questions. Examples are:

- What did you learn from doing this project?

- What did you learn in our conversation today that surprised you?

- How do these objects relate to your B-Mitzvah?

- Would you like to learn more about your family history?

Final Step: Display

You can document this joint B-Mitzvah project in several ways:

- If you are together in person, set up a camera and record the conversation. If you are talking on Zoom, record the session. You might also film yourself separately and send it as a video to one another. (That precludes the possibility of in-the-moment conversation.)

Print out and mount the two photographic portraits together in one frame or in two separate frames displayed next to each other. - Write short artist statements. Include the date, of course, laminate, them, and attach them to the back of the photos, explaining the meaning of each item.

In this way, you have each created a permanent, yet portable, keepsake as a tribute to each other, perhaps adding new depth and insights to your relationship. Once begun, who knows how these conversations may evolve?

Some project examples:

This photograph includes the orange scarf the subject wore in the first passport photo she received as a US citizen; her first dollar bill earned in America; a map of her early life in Eastern Europe; and a copy of Dante’s Inferno, the book her American teacher told her she would one day read though she spoke no English.

At the center of the portrait is a nutcracker, symbolizing the opening of the subject’s childhood memories and the way she would help her grandmother prepare charoset for Passover. She is on the phone because all who know her describe has as “a friendly, talkative person.”

The plant embodies the subject’s nurturing nature. The flashlight symbolizes that her deceased husband “lit the way” for her. Notice how the candlesticks are carefully placed to frame the portrait.

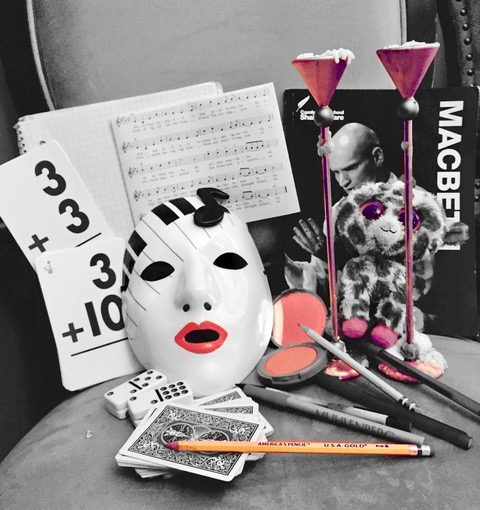

The pink candlesticks represent the subject’s expressed femininity and love of Judaism. Music sheets, mask, and playbook reflect an early and lasting love of theater.

Barbara Ellison Rosenblit has taught widely under the humanities umbrella, including women’s and Jewish history, Tanakh, literature, and Dante, committed to linking subjects and weaving art throughout all these disciplinary silos. Rosenblit is the recipient of the 2004 Covenant Award for excellence in Jewish education, as well as two National Endowment for the Humanities awards, a Japan Teacher Fulbright Award, and the Robert M. Durling Prize for Teaching Dante. She has served on the Board of the Jewish Women’s Archive.

Sheila Miller is an artist and art educator who has been teaching for more than 35 years, utilizing the language of art to explore social, intergenerational, and identity issues with students and adults. She specializes in the integration of art into interdisciplinary curricula, commissioned to design student art exhibitions across the city of Atlanta including in schools, women’s shelters, children’s hospitals, human service agencies, and community clinics.

Starting in 1997, Rosenblit and Miller collaborated on a course, which they taught for 18 years, in which high school students collected life stories of elder Jewish women and translated those interviews into the language of visual art. They documented the impact of this course in the book Pentimento: Revealing Women’s Stories and in a short collection of films about the projects.

Photographic Credits

Photographs by Barbara Rosenblit and Sheila Miller

With gratitude to teen reviewers Liora Pelavin and Annelia Ritter.